Central Bankers Are Sick of Rescuing the World Economy Alone

With limited firepower and bloated balance sheets, central banks say that this time they can’t do it alone.

(Bloomberg) -- Global central bankers are again in the driving seat when it comes to propping up the world economy, but many are demanding governments join them in the rescue effort.

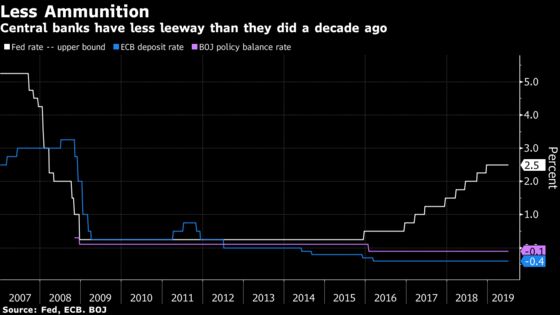

Amid slowing global growth, the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and perhaps even the Bank of Japan are all set to ease monetary policy in coming months. But with less room to act than in the past, their leaders are telling politicians they will need to assist if a downturn takes hold.

The pressure could be applied in person on Wednesday when central bankers and finance ministers from the Group of Seven nations meet for talks north of Paris. They convene at a hazardous juncture for the global economy, as an unpredictable trade war risks precipitating a deeper downturn, and some bond markets hint at a growing possibility of a recession.

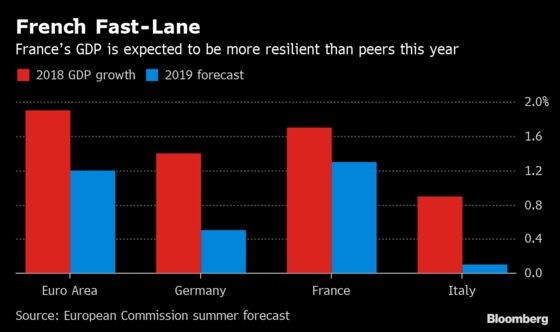

G-7 host nation France may even offer a reason to take note. President Emmanuel Macron’s 17 billion euros ($19.2 billion) of support for consumers in response to the Yellow Vests protests may have been contrary to his deficit-reduction mantra, but is proving fortuitous amid a global slowdown. French growth in 2019 is expected to outpace the euro-area average for the first time in six years.

“We are seeing political risks rising everywhere, so addressing the lack of growth that benefits all is quite urgent,” said Laurence Boone, chief economist at the OECD. “That cannot be achieved only through monetary policy.”

Central banks are already set to play their part to preserve the expansion. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell last week all but confirmed he will cut interest rates this month, while ECB President Mario Draghi is leaning in the same direction.

But with limited firepower and bloated balance sheets, they say that this time they can’t do it alone. The Fed, for example, has a benchmark rate half the level it had before past downturns. The BOJ and ECB are below zero already.

“We would expect to see fiscal policy being the new monetary policy going forward,” said Andrew Bosomworth, a portfolio manager at Pacific Investment Management Co.

While Powell has warned the U.S. fiscal position is unsustainable in the long-run, he said last week it’s “not a good thing to have monetary policy being the main game in town.” The U.S. got a boost in 2018 from President Donald Trump’s $1.5 trillion tax overhaul, but that effect is fading.

Read More:

|

In Europe, Draghi has complained that monetary policy has taken on a “disproportionate’’ burden in the last decade.

Some say the message may be more effectively conveyed by International Monetary Fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde when she replaces Draghi in November. She’s already said that in the next slump, “fiscal stimulus wherever possible” will be needed. BOE Governor Mark Carney, a potential candidate to succeed Lagarde at the IMF, has also pushed the idea.

Their calls have additional weight given the collapse in global bond yields, making it cheaper for governments to borrow. In Europe, much of the focus is on Germany: Not only does it have a budget surplus, but investors will pay it to borrow for up to 15 years.

The big difficulty is high debt ratios. France’s, for example, is close to 100% of output, while Italy’s is even higher.

One euro-area solution, according to the OECD, would be to coordinate fiscal stimulus in some countries with structural reforms in others, in tandem with loose monetary policy. It estimates that a joined-up effort would raise GDP growth by around 0.75 percentage point in this year and next.

It could be in time that central banks and governments do end up uniting if more leftwing parties win election. Some lawmakers in the U.S. and U.K. have promoted Modern Monetary Theory, which posits that countries which control their own currency can seek stronger economic growth via government spending.

“If current non-conventional policies have been a leap forward from traditional measures, the future political landscape could warrant an even more radical shift,” said Alberto Gallo, head of macro strategies at Algebris Investments.

In the meantime, G-7 officials may look to the last crisis, when their governments pulled back from stimulus too quickly. The world economy had barely escaped recession when policy makers meeting in early 2010 agreed to “look ahead to exit strategies and move to a more sustainable fiscal track.”

“For most advanced industrial countries, the monetary policy space is extremely limited,” said Willem Buiter, a former Bank of England policy maker now special economic adviser to Citigroup. “We need the fiscal tools to safeguard ourselves against a possible slide into a global recession.”

--With assistance from Zoe Schneeweiss.

To contact the reporters on this story: William Horobin in Paris at whorobin@bloomberg.net;Simon Kennedy in London at skennedy4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Fergal O'Brien at fobrien@bloomberg.net, Brian Swint

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.